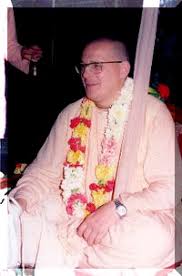

A World Apart: My uncle is a Hare Krishna spiritual master

Profesorado de Yoga 2010

Resultados de la búsqueda

resultados

Resultados de la búsqueda

resultados

Resultados de la búsqueda

resultados

Resultados de la búsqueda

By Chico Harlan

I wasn't quite sure what to expect when I traveled from Washington to an ashram in northern India to meet my uncle, a holy man. Most people who meet him fall to their knees.

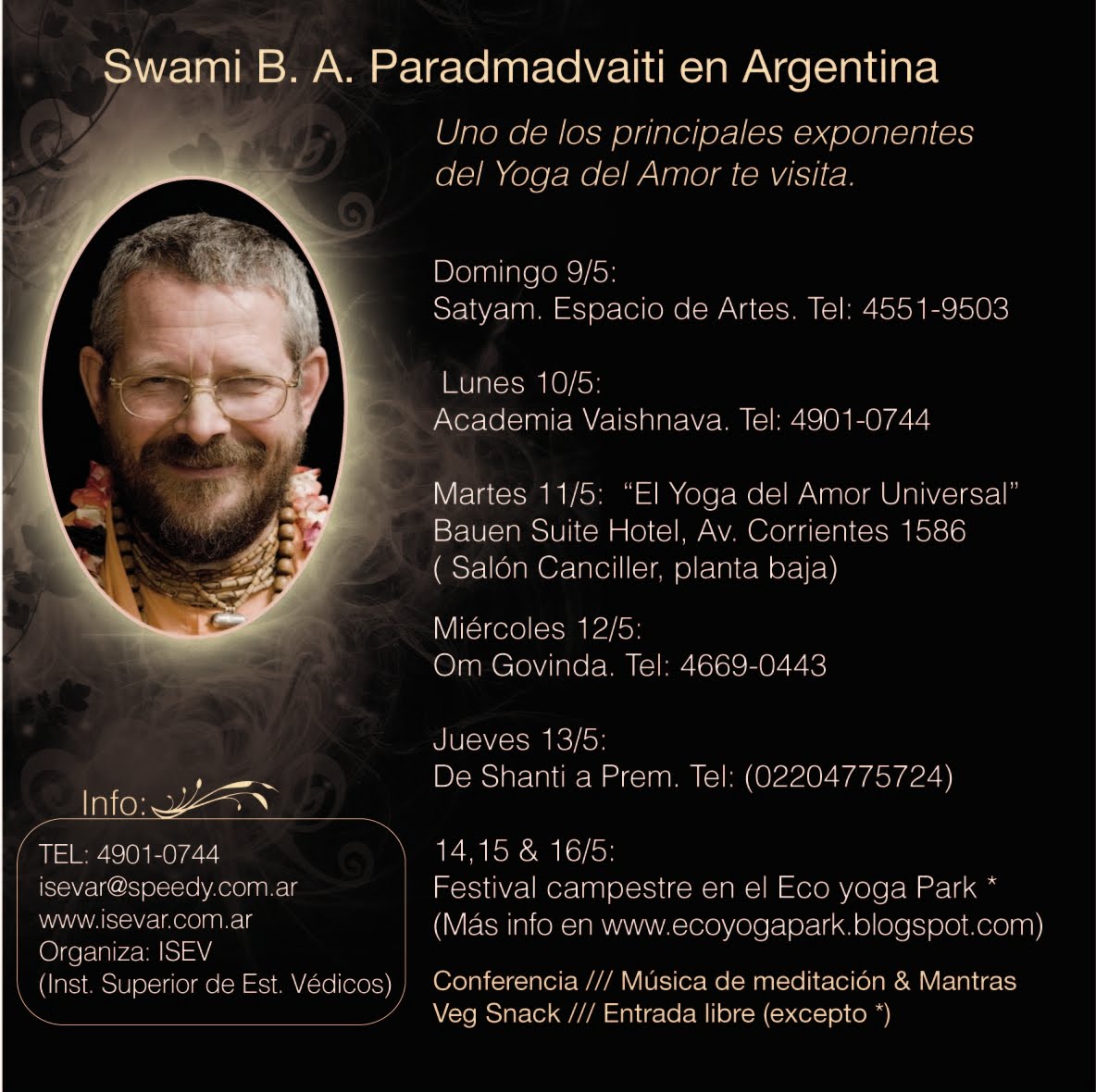

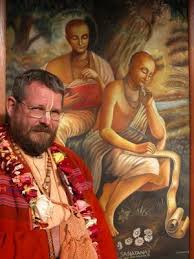

Until the days preceding my flight, I knew little about my father's younger brother beyond his name, or at least his most recent one. He had changed it twice, once when he left the family and became a Hare Krishna monk, and later when he accepted a vow of celibacy and became a spiritual master. He now goes by the name Swami Bhakti Aloka Paramadvaiti.

I'd met him twice before -- for a few hours during childhood and again six years ago when he came to Pittsburgh to visit my family. During the second visit, he refused my mom's cooking because it wasn't pure. He accepted only an apple and consumed it entirely. Seeds, core, everything. Whatever else happened, I remember only how a bearish, ponytailed man, wearing saffron robes and sandals, walked into my house and ate an apple whole.

My uncle has always kept his distance from the family. At one point, he didn't speak to my father for a decade. My dad, the older brother by 1 1/2 years, works as a warehouse executive, drives a Subaru Outback and doesn't mind a cold Yuengling when he gets home. For the past three decades, my uncle, now 56, has rarely spent more than three days in one place. He possesses almost no money. He eats no meat and drinks no alcohol. Those rare times when my father mentions his brother, the tales sound like hearsay: The man has an acute, almost seductive charisma and some untold number of followers. Devotees, rather. People who believe him to be the highest spiritual authority on the planet.

Once, Paramadvaiti went five years without speaking to his own mother. His love of Krishna often has overwhelmed his capacity (or his care) to deal with a family that does not share his faith. As much as my uncle admonishes the material world, though, he also needs to navigate it. As such, he carries a BlackBerry. And that's how he learned of my desire to visit.

In late September 2008, I e-mailed him and explained that I was a 26-year-old reporter who loved a good excuse to travel. I wanted to witness his world and learn about his life. Description of my daily animal protein intake was categorically avoided. About two weeks later, Paramadvaiti wrote back.

Dear chico, Haribol. That means: all glories to the supreme lord in Sanskrit. Yes, I am pleasantly surprised. You can stay with me, travel with me any time. That is a standing invitation. Some locations being more amazing then others. A pilgrims life. For details contact Kalki. In Miami... He is available in our meditation garden.

He sent me a telephone number for Kalki, his assistant, and links to a few blogs about vegetarianism. I booked a flight to India. Then, finally, I started asking questions about the uncle whose blood I share but whose world I did not understand. I wondered how he'd transformed, and to what end. My grandmother had learned to see the virtue in his radical life, because now, in their rare visits, the son who was so combative and miserable as a teen seemed "exuberant" and "very loving," she says.

Paramadvaiti's devotees view him as pious and pure, and they travel the world to meet him. But their absolute devotion raised suspicions in my mind. I'd always joked to my friends, describing my uncle as a comic figure, a could-be cult leader who doesn't have sex. But the reality was more serious. Was he selfless or a fraud? Was he peaceful or dangerous? And what did I, a bit of a wanderer myself, have in common with him?

***

To hear my family tell it, my uncle's world had always been two parts extreme, one part exasperating. Born Oct. 12, 1953, Ulrich Harlan almost always seemed bothered by something, be it asthma or chronic sickness or jealousy of his older brother. Ulrich was the second-born of four siblings, all raised in rural northern Germany.

Though close in age, my father and uncle were as much rivals as friends. My father, studious and compliant, gained the favor of his teachers. My uncle, wild-eyed with curly hair and a penchant for Che and Marx, drew the ire of authority. He ignored his father and paid plenty of attention to drugs. Once, the police arrested him under a bridge as a loiterer. He told his mother: "I just wanted to find out what it feels like when you have no money."

He thought about suicide, got kicked out of school and spoke of moving to Nepal. "Where did I go so wrong?" my grandmother, who still lives in Germany, wrote in her diary back then. One afternoon, terrified of losing her connection with her son, then 17 or 18, my grandmother, a good Lutheran, sat with him at the kitchen table and got high on LSD.

Not long afterward, my uncle found a Krishna ashram--in essence, a decrepit apartment of hippies in Dusseldorf. The small group of devotees lived in the attic. The place didn't have running water, but Paramadvaiti embraced the extreme austerity. "Now at the age of just 18 I had found a monastery without roots in the west," he later wrote on his personal Web site. "All was new. [T]he way we dressed, the music, the master, the food, the books, the daily routine, the haircut ... And I loved it."

My uncle's worldview had found a match. The Krishnas acknowledge the unhappiness of existence. In fact, much of their belief system was founded upon it. "Unless one is inquiring as to why he is suffering, he is not a perfect human being," wrote A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, among the most well-known Krishna spiritual masters. "Humanity begins when this inquiry is awakened within the mind." Krishnas accept as a basic tenet that their spirits are trapped in their body, in the material world, in a labyrinth of impure distractions. The goal is to break free, end an existence of reincarnation and join Krishna in his eternal kingdom.

My family knew of Paramadvaiti's conversion in part because he attempted furiously to convert them. Several times each year, especially in the 1970s, my uncle wrote letters lecturing his mother about her empty life. In one, penned in 1973, he spent about 500 words instructing her to stop cooking meat and start chanting the holy mantra. Then, just before signing off, he suggested she buy from him high-grade rosewood oil and incense. A decade of my grandmother's resistance did not dull Paramadvaiti's preaching (he has relented only in recent years).

Each letter began, "Hare Krishna! All Glories to Srila Prabhupada." He no longer signed his name, "Ulli." He was, in all respects, no longer a Harlan.

***

When I got off the plane in New Delhi, India, it was 3 a.m. White soot clouded the inside of the airport terminal. Somebody had heard gunshots indoors several hours earlier, and men with resplendent mustaches gripped machine guns to their shoulders. A shrieking ambush of cabdrivers pleaded: "Where to, sir? Where to? I take you, yes?"

My uncle was four hours south, by taxi, in a village called Vrindavan. There, at an ashram called Vrinda Kunj, he was staying with dozens of devotees. I wondered: Was I visiting an uncle or a god? I hopped into a cab. When the driver asked why I'd come to India, I said, as if to wish it were true, that I was visiting family.

After four hours, we bounced into Vrindavan, up and down through the Old World decay: Krishna temples, beautiful and destroyed; rhesus monkeys hanging from electric wires; piles of plastic litter; kids urinating in the streets. Alleyways led to smaller alleyways, and finally, at the last doorway of the universe, there he was--Paramadvaiti, thank God.

He rose when he saw me. He was fleshy as a papaya and far bigger than anybody else in my family. We shared an uncertain hug--quick, first-datish --and he showed me to the upstairs room where I would spend the next 10 days. We sat down on opposite sides of my bed. I said nothing. He operated with great comfort in silence, and the silence hung there long enough for me to wonder what he was wondering. The silence: My uncle just inhaled it, holding it, until at last he exhaled and smiled. The smile, tugging at every crease of his face, caught me off guard. It was the kind of smile that said: I could sit here all day on this hard bed and say nothing. It was also the kind of smile that said: I am the rare man who can prove his authority with silence.

When the big man finally deigned it time to talk, my much-rehearsed plan for the First Conversation was in smithereens. I had outlined my talking points: I could tell him about the little flashes in my own life where I took risks, as he had, or felt lost. I could tell him about quitting my comfy job in 2007 and heading for seven months to Australia. I could show him my backpack, stuffed with goodies that emphasized the overlap of our separate lives. Socks that my grandmother knitted for him. Fresh family photos. Old letters he'd sent to my grandmother.

Of course, I realized then that these were relics from a past life, and unveiling them might be a poor way to demonstrate my modest sense of enlightenment and material distaste. The revised plan was to, more or less, shut up and listen.

Paramadvaiti needed no prodding. With measured and formal words, he spent several minutes describing life at the ashram, where austerity applied to almost everything, including the toilets, which lacked seats. We wake up for daily 5 a.m. meditation and chanting, he explained. We think constantly about God.

My uncle paused. His next words sounded unsteady, or even awkward. My uncle... well, he sort of apologized. "I realize, yes, that I have not been such a present part of the family," he said. I nodded. He patted me on my knee.

"Sometimes, the Krishna community and the birth family are diametrically opposed obligations. Maybe this, these next days, I can make up for my absence as an uncle. Yes?"

I barely had the chance to respond, because the door to my room swung half-open, and a waifish woman, perfect olive skin, maybe 23 or 24, robed in a psychedelic purple shawl, stuck her nose in to have a look. Paramadvaiti abandoned the family talk and waved her inside, coaxing a few tentative steps. The woman moved toward him like a child approaching a cave, but she did not look scared. Rather, she glowed. When she got within an arm's length of my uncle, she dropped to her knees, genuflecting at his feet. I just sat there, still silent, and wondered, if only momentarily, whether it would be appropriate to join her.

Paramadvaiti soon suggested we eat lunch with a small group of devotees. Five of us settled at an outdoor table overlooking the ashram garden, and everybody waited for their leader to talk/preach/educate, which he never did. Evidently, he was just hungry. While others ate a yellowish spread of rice and root vegetables, Paramadvaiti received a bounty: soup, beets, ginger tea, breads, floury sugar nuggets for dessert. He munched even while others waited for their food.

We didn't get far with family talk. Meal complete, a servant arrived with a saucepan of water and a hand towel; Paramadvaiti alone washed his hands. Everybody but my uncle shared in the dishwashing.

***

The next morning, after an hour of pre-sunrise chanting, my uncle taught his daily class in the ashram temple. More than a dozen devotees--the entire ashram population--fanned out in front of their guru on the floor. Paramadvaiti lowered himself onto a throne-like seat cushion and promptly decided to prologue the day's wisdom with a medical report.

"I am still pumping out mucus," he said.

For several days, my uncle had fought a cold, and just about everybody at Vrinda Kunj knew this because he blew his nose with no discretion, as if the honking itself was an urgent message from God. Before beginning his lecture, he grabbed a tissue and tromboned. "Fetch me some ginger," he said to nobody in particular. A devotee scurried off to the kitchen.

When these devotees addressed my uncle, they called him "Guru Maharaj," which, at least semantically, is a little like King of Kings. He is revered because of his title ("swami") and his vow to forsake sex and material possessions, which is considered the highest level of spiritual purity and devotion.

The followers had taken spiritual names, and they considered themselves servants to any number of higher authorities, a line that started with my uncle and traced back to Lord Krishna. Most of the devotees were between 20 and 30 years old, a mix of men and women, and many had traveled from South America and Europe.

The lone American devotee there, raised in West Virginia, had arrived one month earlier carrying one suitcase, the sum of his belongings; he had sold his Honda Civic, MP3 player and almost all of his clothing to fund the pilgrimage. Another devotee, from Germany, had spent his teenage years in anguish, always on drugs, sometimes so depressed that he thought he was dying, he said. On the day he met Paramadvaiti at an ashram in Europe--his first exposure to Krishna Consciousness--he finally saw a way to combat the distress of the world. He begged to move into an ashram. He took all the pledges of devotion. That day, his drug use ended, he said. Five a.m. was now wake-up time, not bedtime.

Paramadvaiti's followers honored their guru in part by spending lots of time on the Internet. They recorded audio and video files of his teachings, given in any of the six languages he speaks -- English, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Swedish and Hindi--and posted them on the Web. Certain blogs catalogued my uncle's travel schedule, allowing devotees to plan their movement accordingly. YouTube videos charted almost every minute that Paramadvaiti danced, sang, lectured, debated, smiled or hoisted darling infants into the air to bless them.

From the moment I arrived, Paramadvaiti's devotees welcomed me with great interest. For several reasons, I was a novelty. I more or less found the world tolerable. I view my own religion, Judaism (the faith I took from my mother), as a small part of my identity, not as the basis for my existence. Most of the devotees assumed that a spiritual emptiness had driven me to India, and even when I rejected this notion, they responded, without fail, that Lord Krishna could work in mysterious ways, and that I should just trust his will and thank him for bringing me. "You know, you have a very special person as an uncle," one devotee, a Chilean named Paramananda Das, would later tell me. "When I have trouble, the first person I think of is your uncle."

"How many devotees does he have?" I asked.

Long pause. "Ten thousand, I'd say." There was some whispered discussion in Spanish with another devotee, then a confirmation.

"First time I met him, when he crossed through the door of my temple [in Chile], I thought, 'Krishna is coming. Krishna is coming.' He is not a rich man hiding poor. He has honesty and faith. All grace. His face makes you happy. Guru Maharaj makes me happy. Not materially happy. Completely happy."

When Paramadvaiti began his lecture on this particular morning, the devotees --barefoot, legs crossed--gazed up at my uncle in a way that kind of made me think of baby birds in a nest. My uncle began his lectures, I later learned, with no particular direction in mind, calling only on the wisdom of Lord Krishna to guide him. As such, these morning sessions sometimes included tangents regarding organic farming, ancient Vedic underwater bridges, carbon footprints, harmony fairs, monoculture cropping, childhood stories, vegetarianism and the shortsightedness of marriage, because no union between human beings can replace the need of service to God.

"You can only find grace by attaching yourself to a fountain of unlimited grace," he said. "I had many friends before this, and they disappeared. They disappeared easily. ... There's too much ego in family. That's why we renounce the family. You need a higher, universal family."

At moments like this, when my uncle wanted profundity, he reached deep into some reservoir no other Harlan could access. His voice worked like a bagpipe, rich with crashing lows, lilting thrusts and pauses just long enough to let everybody brace for a tumble of wisdom. Depending on his mood, he could speak faster or slower than anybody else I knew. He had a habit of removing his glasses to punctuate a point. He also had a curious method, I realized, of winding his lectures back to their starting point.

"We are not here to stay," he said.

Again, with feeling: "We are not here to stay!"

He flung his right hand from his body.

"Like the soul and the body. Like the nose and the mucus. Yes, it's the same region, the same part of the body, but the mucus, it needs to get out. Everything in your body eventually withdraws. Your health withdraws. Your beloved withdraw. All matter withdraws."

***

Midway through my stay, Paramadvaiti decided to acquaint me with India by way of a shopping trip. "Come, I'm taking you on a tour," he said.

His eyes glowed with mischievousness, and we headed toward the Vrindavan bazaars. My uncle moved down the cobblestone streets, through all the human and bovine traffic, with the sort of relaxed, dignified majesty that I can only call papal. He greeted just about everybody with an obliging half-bow, hands clasped in thanks, and wore the usual robe and greenish Crocs. His BlackBerry was tucked in a side pocket.

At first, I reasoned that Paramadvaiti took me shopping to appease the presumed wishes of his Western guest. But our arrival at the north end of the cluttered bazaar terminal suggested otherwise; we were greeted by thronging stalls filled with pirated technology, faux gold Krishna deities, fried street food, rugs, T-shirts and gilded jewelry, and I posit now that no anti-materialist has ever gotten more excited to view a full display case of sparkling plastic bracelets.

"How much?" Paramadvaiti asked one vendor, holding a purplish bracelet.

"Four hundred rupees."

He kept walking. Within minutes, though, we had collected an allotment of high-value supplies, including natural cold medication (with cardamom), decorative felt banners declaring the Krishna mantra, and a handwoven rug for my mother, available from a haber-dasher named Dinish, who gave us a good discount on account of my uncle.

"This is just beautiful craftsmanship," my uncle said, petting the fabric.

The shopping ended. Our bonding did not. We were having a good old time, and for the first time Paramadvaiti was introducing me as his nephew. After stop-offs at a few temples, we wound down a quiet alley, cast in the last orange flickers of daylight. Paramadvaiti stopped at a green metal door, one in a long line of narrow, dilapidated houses. He knocked. Two women answered. They saw Paramadvaiti and gasped. We walked into their home, and the women --one slender, one round--just about clung to the walls, as if in need of balance. Each woman covered her mouth. Paramadvaiti showed his widest smile, hands back in prayer position.

"Haribol! Haribol!" he said. Greetings, greetings.

The women said nothing. The entrance room of their house was all cold concrete, a hard bed in one corner, a bucket in another. A narrow staircase led upward, and Paramadvaiti followed the women until we arrived at a makeshift Krishna shrine. A blue deity stood, sentry-like, in the middle of what looked like a bathtub covered by drapes. Detergent and an empty bottle of Minute-Maid aligned at the side of the tub. The women glanced at the porcelain scene, then glanced at Paramadvaiti.

He gazed at the bathtub deity for 90 seconds, and it was a gaze I recognized-- unconditional. He told the women they had done something beautiful. "Krishna Krishna Krishna," he muttered, and he lowered himself to the ground, bowing toward the bathtub. Then, Paramadvaiti excused himself, ducking down the hall into a bathroom.

While my uncle was gone, the slender woman whispered a few words to me in her broken English: "Lucky," she said. "You are lucky. Follow your uncle. He knows where to go. Always, he can go -- how you say? His soul. Shastra, you know. Follow his soul, and you will be happy."

The rounder woman hurried back down the stairs, and when, after about five minutes, Paramadvaiti reemerged from the bathroom, we returned to the concrete entrance room and took spots on the hard bed. The round woman handed us a platter of flaky sesame seed sticks--a concentration of sugar, like the innards of a Butterfinger. The women giggled as we ate. Paramadvaiti commented that the food was good but that we should be hurrying along. We left about 10 minutes after arriving, having done no more than eat their food and use their toilet. My uncle slung his arm around me. As we walked down the narrow pathway, I asked him why he'd knocked on their door.

"Spiritual life, it's amazing," he said. "Did you see those women? They were vibrating with joy."

But I wondered about the biggest contradiction of all in the worldly life of Swami Bhakti Aloka Paramadvaiti. By supposedly disassociating himself from his ego, he just so happened to discover a life that indulged it. By relinquishing everything, he gained everything. My family members, especially my father and my aunt, wondered, too, how my uncle drew the line between purity and hypocrisy. Devotees sometimes spent 30 minutes on the floor of Paramadvaiti's office, rubbing their guru's feet. Nobody second-guessed his teachings. In every room, he was accepted as the greatest and smartest, a convenient platform for a man whose humility prevents him from saying as much.

How backward that a man, miserable among his happy family, could find happiness in the places where many would find only misery. Others recognized this, too. When my grandmother visited Paramadvaiti in Germany in 1983 and spent time with him for the first time in five years, the combativeness that drove her crazy when Ulrich was a teen seemed to have disappeared. "He appeared as a person who has found his true destiny," she later wrote in a letter. "The Krishna movement turned this torn, unhappy young man into an exuberant, disciplined, well-balanced and very loving person."

After our shopping trip, I felt more comfortable asking my uncle questions. Though it was sometimes hard to grab his undivided attention--several devotees every hour came into his office for counsel--he answered frankly about his childhood.

Yes, he acknowledged, he had been a troubled boy. At age 10, while playing in a barn, a friend pointed a gun at him and pulled the trigger. The gun wasn't loaded, but an accumulation of mortar discharged and flew into my uncle's eye. For months, he lay in the hospital. Doctors feared for his vision. The family, driving in from the countryside, visited him once every two weeks.

"They had me strapped, strapped to the bed," my uncle recalled. "All my family, they said, 'Oh, this poor boy, he cannot move his body.' So what did they do? Feed me chocolate. And when I came out of the hospital, I was round like a bottle, with one eye looking this way and another eye looking that way."

As a child, Ulrich clashed with his father, a teacher. The man could talk for hours about bird-watching, but he couldn't once say, "I love you." He had the warmth of a science text. And when Ulrich once wrote a biting school report on the failings of his father, he showed it to the target himself, who said only that it was well-written.

When my uncle first became a Hare Krishna in 1972, he was the servant to the servant, a devotee of Srila Prabhupada. Others ordered my uncle to travel, and he obeyed. He owned neither his own time nor space. He had surrendered his ability to make choices. A South American woman, a fellow follower, fell in love with him and wanted marriage. But love between two people who do not share a connection with God -- and whose relationship is not built as a means to religious pursuits--will invariably end up grasping for something false, he says. He couldn't marry her. Krishna was the Supreme Enjoyer.

Paramadvaiti crisscrossed South America setting up temples for the mission, and he was good at it, a talent that triggered his rise through the faith. But Krishna members, at the time, faced persecution across the globe. He was jailed in Argentina and Paraguay, told only that the government prohibited all religions except Catholicism, he said.

One guard with a particular zeal for torture dragged Paramadvaiti into the jailhouse bathroom and ordered him to wipe feces off the floor. Paramadvaiti clawed for his spiritual strength, until at last he realized that Lord Krishna must have willed this feces-cleaning, because it taught a lesson about pride, and no man should be too proud to obey orders. So Paramadvaiti... well, he kept on cleaning, and he even grew kind of happy.

"The torture guy came back, probably expecting some monk to be in there looking all miserable, and he sees me like this," Paramadvaiti recalled. "Yes, I was happy!" He lowered his voice to a conspiratorial whisper: "I think I blew his mind."

***

On my final full day in India, my uncle and I conducted the big face-to-face talk, though technically this was done face-to-foot. Paramadvaiti sat on the only chair in his office, and I sat on a straw floor mat, volleying questions. Until this moment, I'd been the one doing all the asking. Now, it was his turn.

"You strike me as an educated young man," he said.

"Yes, I guess so."

"So," he said, "how can somebody like you just stand back and watch?"

Perhaps every pilgrimage brings the seeker to that final vista, a place where he looks back on what brought him there and realizes something, either profound or foolish. There I was, interviewing, probing, trying to understand the dynamic of a relationship I never heretofore even cared about--and why?

I tried to answer his question, but the words were clumsy. I told him, more or less, that I didn't yet know my beliefs. Nothing I've been exposed to has prepared me for--or made me desire--a life of complete immersion and devotion. I enjoy traveling, going to concerts, having coffee and beer with friends, occasionally talking about the AFC North instead of God. I recognized in Paramadvaiti just a small fraction of myself, but I wanted no part of his devotion to the extreme, no matter how peaceful he seemed. "Frankly," I said, "it scares me a little."

He just nodded.

Maybe he already understood the part I left unsaid. The part about me that I was not ready to admit. Maybe my motives weren't as pure as I wanted them to be. Maybe my curiosity about my uncle was just the cover for a convenient excuse to travel. Maybe I didn't give a darn how this conversation went. Maybe I was here for one reason, a reason that had everything to do with ego and control: I wanted to go home and write about this trip.

The next day when my uncle and I parted, we returned to what we knew. He would deal with a canceled flight to Finland, resigning himself to a sleepless night at the New Delhi airport, because penniless monks don't have the money for hotel rooms.

I headed back to Washington by way of Frankfurt, stopping on the layover to buy cold medicine and a Rolling Stone. As I boarded a final plane to Dulles, the gap between my uncle and me, again, reformed into something unbridgeable. It was a gap made of miles and time zones, sure. But it was, too, a gap between desires: my desire to see something and his insatiable desire to know it.

I saw. For me, it was enough.

Chico Harlan is The Post's new Asia correspondent. He can be reached atharlanc@washpost.com.

Links:

http://harijanmandir.blogspot.com/ - Referencias

http://yogesvara.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de YOGESVARA

http://vrindablog.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de Noticias de VRINDA

http://gurumaharaj.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de Gurumaharaj.net

http://gurumaharajdiary.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de Swami BA Paramadvaiti diary

http://ecoyogapark.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de Eco Yoga Park

http://vrindatucumanmandir.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de Misión Vrinda de Tucumán

http://eltamborrugiente.blogspot.com/ - Más resultados de El Tambor Rugiente - Referencias

http://vrindacalendario.blogspot.com/

http://www.wryndawana.pl/ - Más resultados de Wryndawana.pl

http://www.officebap.com/vrindatv/ - Más resultados de Vrinda TV - Referencias

Página PRINCIPAL

OBRAS y AUTORES CLÁSICOS

Agradecimientos

Cuadro General

Disculpen las Molestias

| Conceptos Hinduistas (1428)SC

|

|---|

|

Category:Hindu (mythology) (3256)SC | Category:Hindu mythology (3270)SC | Categoría:Mitología hindú (3288)SC (indice) | Categoría:Mitología hindú (videos) (3289)SC | Conceptos Hinduista (A - G) SK y SC (videos) (3294)SC

Aa-Anc · Aga - Ahy · Ai - Akshay · Akshe - Amshum · Ana - Ancie · Ang - Asvayu · Ata - Az · Baa-Baz · Be-Bhak · Bhal-Bu · C · Daa-Daz · De · Dha-Dry · Du-Dy · E · F · Gaa-Gayu · Ge-Gy · Ha-He · Hi-Hy · I · J · K · Ka - Kam · Kan - Khatu · Ki - Ko · Kr - Ku · L · M · N · O · P · R · S · Saa-San · Sap-Shy · Si-Sy · Ta - Te · U · V · Ve-Vy · Y · Z |

| Conceptos Hinduistas (2919)SK | (2592)SK

|

|---|

|

Aa-Ag · Ah-Am · Ana-Anc · And-Anu · Ap-Ar · As-Ax · Ay-Az · Baa-Baq · Bar-Baz · Be-Bhak · Bhal-Bhy · Bo-Bu · Bra · Brh-Bry · Bu-Bz · Caa-Caq · Car-Cay · Ce-Cha · Che-Chi · Cho-Chu · Ci-Cn · Co-Cy · Daa-Dan · Dar-Day · De · Dha-Dny · Do-Dy · Ea-Eo · Ep-Ez · Faa-Fy · Gaa-Gaq · Gar-Gaz · Ge-Gn · Go · Gra-Gy · Haa-Haq · Har-Haz · He-Hindk · Hindu-Histo · Ho-Hy · Ia-Iq · Ir-Is · It-Iy · Jaa-Jaq · Jar-Jay · Je-Jn · Jo-Jy · Kaa-Kaq · Kar-Kaz · Ke-Kh · Ko · Kr · Ku - Kz · Laa-Laq · Lar-Lay · Le-Ln · Lo-Ly · Maa-Mag · Mah · Mai-Maj · Mak-Maq · Mar-Maz · Mb-Mn · Mo-Mz · Naa-Naq · Nar-Naz · Nb-Nn · No-Nz · Oa-Oz · Paa-Paq · Par-Paz · Pe-Ph · Po-Py · Raa-Raq · Rar-Raz · Re-Rn · Ro-Ry · Saa-Sam · San-Sar · Sas-Sg · Sha-Shy · Sia-Sil · Sim-Sn · So - Sq · Sr - St · Su-Sz · Taa-Taq · Tar-Tay · Te-Tn · To-Ty · Ua-Uq · Ur-Us · Vaa-Vaq · Var-Vaz · Ve · Vi-Vn · Vo-Vy · Waa-Wi · Wo-Wy · Yaa-Yav · Ye-Yiy · Yo-Yu · Zaa-Zy |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario